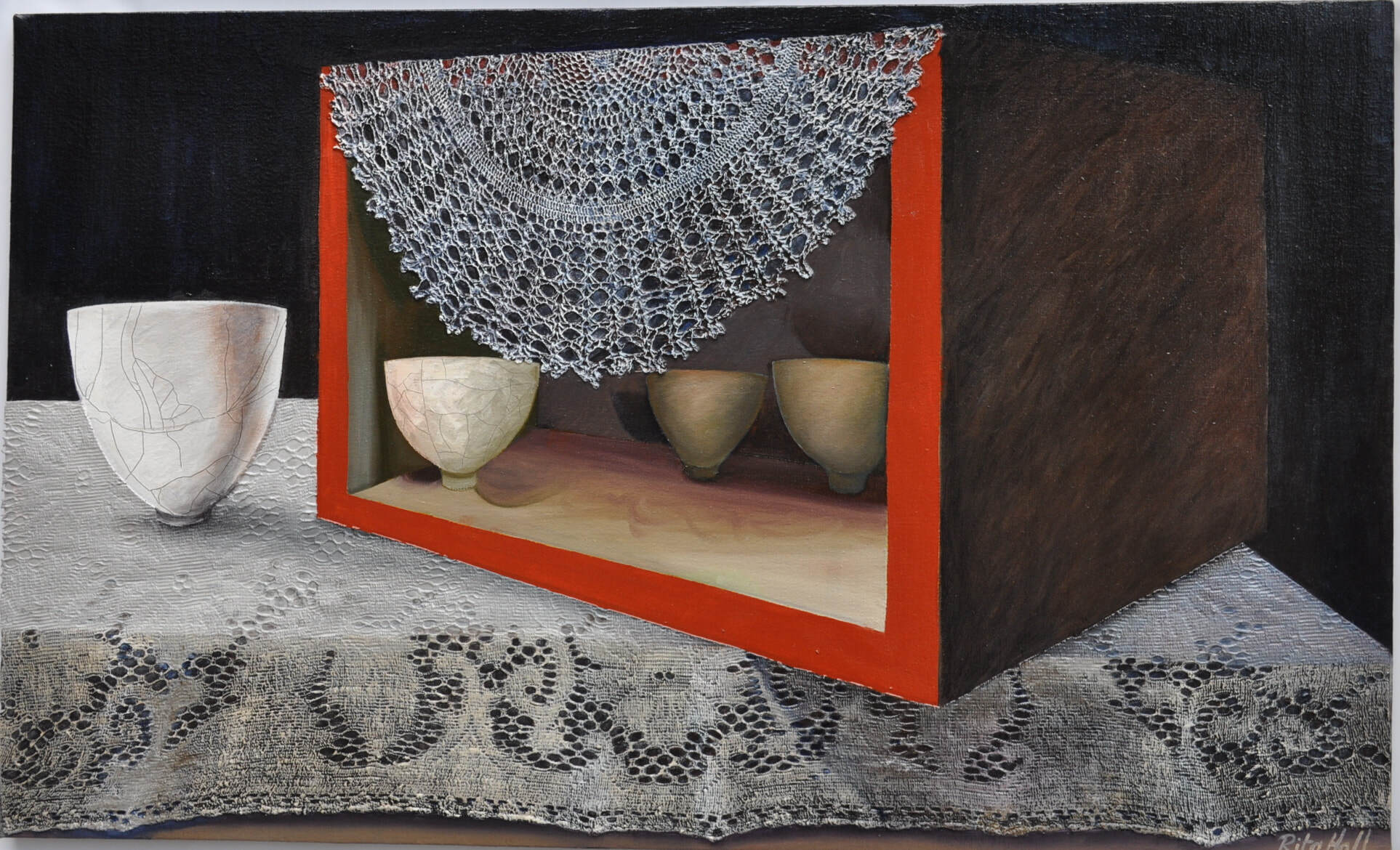

The domestic ritual is not immediately recognisable as ritual or obeisance; nor is it known by formal titles or commonly shared cultural or social meanings. Every participant makes his or her own habitual performance in relation to domestic rituals. These are inherently personal yet public, and often performed as gestures of love or necessity. They involve recognisable artifacts; the rituals are within the objects and their use value. It is in the heart of a bowl, the surface texture of the lace cloth, and the covering of the table. It is the memory and expectation of a sigh, the movement of light across the kitchen floor or the domestic space as the light fades.

The domestic space, once considered essentially feminine, is ruptured and struck down by representations of it as multi-purpose, a place for working, and for talking, or for seeing the shape of an object as more than the simple activity is was designed for. It is a space captured by these works as partial with the possibility of each speaking to a moment or passing comment. The titles of the works speak to the impermanence of ritual, the shifting meanings of objects.

To be ritualized is to be set apart from the ordinary, yet the labor of painting is also a ritual of training and alignment. Here the object becomes the carrier of your own meanings, they strain against the over-determined nature of viewing, they could be simply forms but here is the taking of forms outside of themselves and asking them to reflect back to the viewer the meaning that you want to put onto each form as it is captured in juxtaposition with others.

The works here take form out of its resting place, bringing it to view as a shape alongside other shapes and objects. Constructing the works into a collage makes sense of them as domestic objects, but here they are not referenced as such. They don’t only tell a story of the domestic; the domestic is a loose connection, but remembrance overlays the works with a kind of gesture towards a past familiar, a future unknown.

Why position these objects and familiar items together? Doing this makes them work together to produce a new set of meanings, arranging them ostensibly as still life is of course the obvious intention but the disparate nature of frame within frame, box within frame, the bowl as a frame, the box or the cushion as a frame for a sleeping head, where you lie your head, the comfort of the cushion, the placement of a teapot on a cushion, the over-arching desires for comfort, isn’t this after all what rituals provide, a source of emotional, physical or spiritual comfort?

The resonances of the feminine and the purposeful ways of keeping house, of house keeping as object keeping, seen in the lines of the cloth, the bowl, the table, or the cushion, these enhance the role of the objects, as they become ritualized in their re-presentation in these works. What do we see here? Labor, memory, objects, impossible arrangements, collage, and painting as a way to see anew and to ascribe the notion of ritual.

Rituals work to routinise and to repeat, the notion of a ritual is part of an observance and in our never ending observance we want to resist the arrangement and the suggestion that we are partaking in a ritual. Yet here we stand looking on at the work of a ritual organization of objects that echoes all of our pre-ordained ideas about what art should be, but disturbs us with its impossible symmetry and placement of incoherent objects side by side.

Rosslyn Prosser 2015